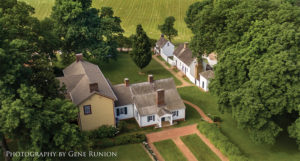

Highland is a historic place with an ongoing story. The former plantation, nestled in the hills of Albemarle County, is like many sites of its kind, both unique and typical in the landscape of American history. Highland was a working plantation in the early American economy, and home to scores of enslaved men, women, and children who performed the bulk of Highland’s production and maintenance.

Highland is a historic place with an ongoing story. The former plantation, nestled in the hills of Albemarle County, is like many sites of its kind, both unique and typical in the landscape of American history. Highland was a working plantation in the early American economy, and home to scores of enslaved men, women, and children who performed the bulk of Highland’s production and maintenance.

From 1799 to 1826 Highland was the sporadic residence of fifth president James Monroe. For years, public understanding of the site relied on incomplete evidence—so much so that a good deal of Highland’s story remained mysteriously hidden! Now historians and archaeologists are peeling back the layers of mystery and misunderstanding to uncover more of Highland’s past. The untold lives of enslaved people, a fire that destroyed the original main residence, alterations by later owners: these are some of the many stories coming to light in recent work by a research team asking the right questions.

Highland Changing Hands

The estate that is called Highland has changed size, shape, configuration, and even name as it has changed owners over the years. The footprint of the remaining house has likewise grown and changed. As recent archaeological work has shown, many of these changes have not always been clearly recorded or widely known! In brief, the story goes like this:

The estate that is called Highland has changed size, shape, configuration, and even name as it has changed owners over the years. The footprint of the remaining house has likewise grown and changed. As recent archaeological work has shown, many of these changes have not always been clearly recorded or widely known! In brief, the story goes like this:

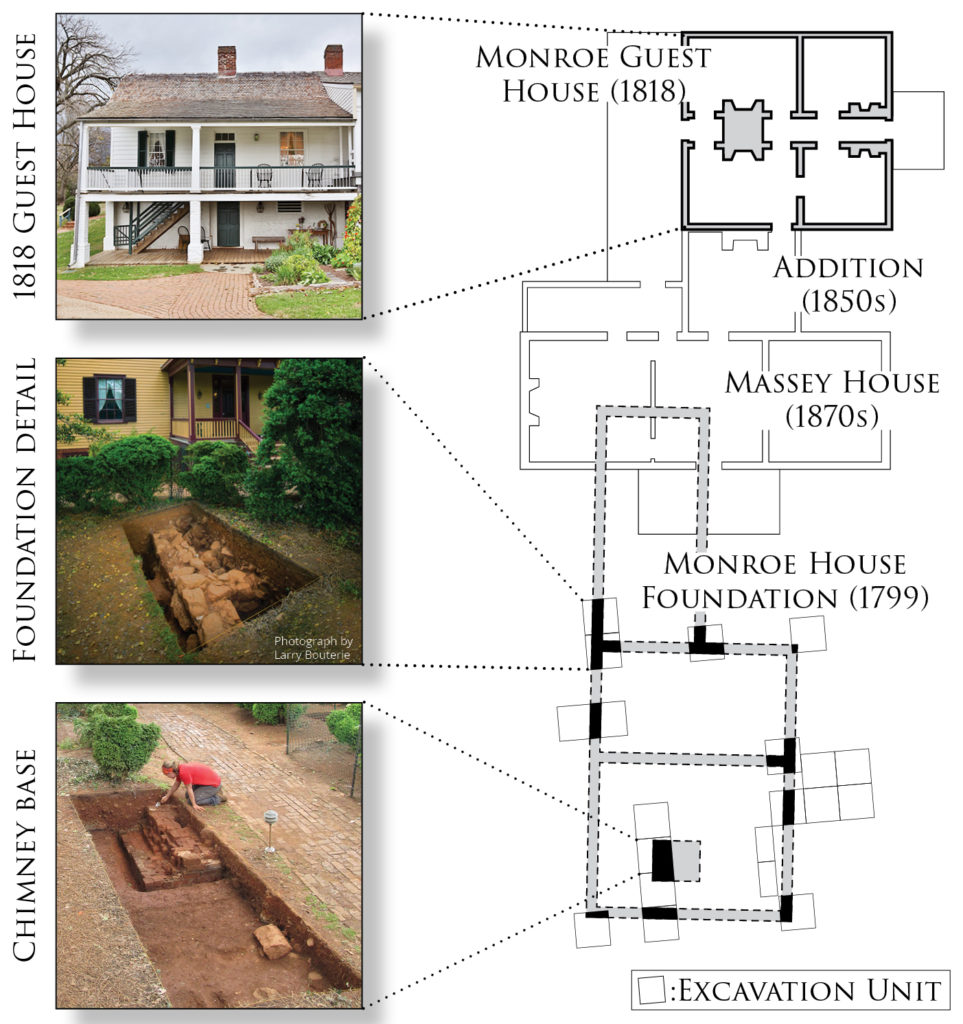

James Monroe purchased 1000 acres of land in Albemarle County at the urging of Thomas Jefferson, his friend at nearby Monticello. Construction started on Highland’s main house in 1797, and the Monroes moved in during November 1799. The main section was one story with finished garret space above, and a wing that housed a kitchen. In 1818 a separate, two-room guesthouse was built to accommodate visitors. In 1826, Monroe sold Highland’s core acreage to one Edward Goodwin, and the rest was sold by the Bank of the United States two years later. It seems that Goodwin was not in residence for long before the main house burned down, likely late in 1829, at which point the guest house became the main residential building. At some point, this guesthouse became widely thought of as a surviving wing of the original house belonging to James Monroe, and that erroneous notion persisted until 2016 when its purpose became more clearly understood. But more on that in a moment!

Highland changed hands a number of times after Goodwin’s ownership. During this time it began to be referred to as “Ash Lawn.” By the 1840s, a porch was added on the southern face of the guesthouse–now the main building–which reoriented the facade of the house towards the workyard. In the mid-1850s a one room addition and corresponding basement were built to expand living space in the guesthouse. Reverend John E. Massey purchased the property in 1867. In 1873, he added the tall yellow farmhouse with the front door and inviting porch, attached to the 1850s addition and overlapping the site of Monroe’s original house.

Massey’s heirs sold the property to Jay Winston Johns in 1930. In 1974, Highland was given to William & Mary by bequest of Johns’ will. The site continued to be known as Ash Lawn, then as Ash Lawn-Highland, until 2016 when William & Mary restored Monroe’s original name: Highland.

New Discoveries Announced in 2016

What made archaeologists start digging, and what did they discover? Sometimes, a fresh look at an old problem reveals the whole story. Highland’s administration changed in 2012, which prompted the Highland team to re-examine the site. This re-examination yielded clues that called into question the inherited story of the small white house said to be the surviving wing of Monroe’s 1799 home.

What made archaeologists start digging, and what did they discover? Sometimes, a fresh look at an old problem reveals the whole story. Highland’s administration changed in 2012, which prompted the Highland team to re-examine the site. This re-examination yielded clues that called into question the inherited story of the small white house said to be the surviving wing of Monroe’s 1799 home.

Continued research then uncovered the foundation of a previously forgotten structure: the 1799 main house, preserved just below the ground surface! With the addition of dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, the researchers determined that the small white house was not attached to the original house but a separate guesthouse built in 1818. A fire seems to have destroyed the main house late in 1829, just a few years after Monroe sold it. An incorrect story about the house’s partial survival had taken root by the 1880s. This research discovery is transforming our understanding of Highland and the way its people lived when they were here.

The Story Revised

What clues did the research team use to determine that the guesthouse was a separate structure? In addition to excavation, researchers relied on two major sources of evidence: architectural clues and documentary evidence.

What clues did the research team use to determine that the guesthouse was a separate structure? In addition to excavation, researchers relied on two major sources of evidence: architectural clues and documentary evidence.

Several architectural clues indicated that the guesthouse was never attached to the 1799 home, but was built as a freestanding unit. Details in the rafters of the guesthouse reveal that its east wall was never attached to another building. Furthermore, the pattern of brickwork in the foundation, the house’s moldings, and its butt hinges all pointed to a construction date in the early 1800s, not in the 1790s, like the Monroe main house. Dendrochronology, or dating using patterns of growth rings in wood, also indicated that the timber for building the guesthouse was harvested between 1815 and 1818 –again, after the main house construction in 1799.

Our most important piece of documentary evidence about the date and construction of the guesthouse comes from a letter from Monroe to his son-in-law George Hay, written on September 6th, 1818. In it, Monroe writes that he has two enslaved craftsmen, a man named George, and a carpenter we understand to be Peter Malorry (historic spelling), building a two-room house for guests on his property.

New Perspectives

How does this new research add to Highland’s story? In correcting the century-long misinterpretation of the 1818 Presidential Guesthouse, we gain a clearer picture of the architectural changes that have happened at Highland over time. In addition the documentary evidence reveals precious facts about the identities of enslaved craftsmen Peter Malorry and George, whose last name is likely Williams. The details of the lives of enslaved people are often left out of recorded history even though, as with myriad other historical sites, Highland’s enslaved men and women were key actors in the running, maintenance, and construction of this plantation. Research like the 2016 project allows sites like Highland to understand the complex communities of people that make up their histories.

How does this new research add to Highland’s story? In correcting the century-long misinterpretation of the 1818 Presidential Guesthouse, we gain a clearer picture of the architectural changes that have happened at Highland over time. In addition the documentary evidence reveals precious facts about the identities of enslaved craftsmen Peter Malorry and George, whose last name is likely Williams. The details of the lives of enslaved people are often left out of recorded history even though, as with myriad other historical sites, Highland’s enslaved men and women were key actors in the running, maintenance, and construction of this plantation. Research like the 2016 project allows sites like Highland to understand the complex communities of people that make up their histories.