– Message of President James Monroe at the commencement of the first session of the 18th Congress (The Monroe Doctrine) December 2, 1823 (in the collection of the National Archives).

“We shall either be a united people, more strongly bound by a common danger, or we shall become a prey to foreign influence.”

– Abigail Adams to John Adams, April 5, 1797.

Independence brought the United States into a world dominated by European empires, each with interests in the western hemisphere. The United States desired to balance trade with these empires while steering “clear of European contentions,” as Thomas Paine cautioned in Common Sense. European contentions, President James Monroe learned, often boiled over into the Americas. During his second term, James Monroe feared Spain might reassert its control over newly independent Latin American countries. British Foreign Minister George Canning feared this as well, and suggested that the United States sign a joint declaration with Great Britain protecting the western hemisphere from Spanish intervention. At the advice of Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, however, Monroe declined. Instead, he pursued similar objectives, without the alliance, in his seventh annual address to Congress. Part of this speech, known as the Monroe Doctrine, was the culmination of decades of diplomatic experience and political ideology. In short, it separated the two hemispheres by preserving Latin American independence and asserting non-intervention by European powers.

Though the Monroe Doctrine allowed newly independent Latin American republics to pursue their own destinies without interference from European nations, it also paved the way for American imperialism. By committing the Untied States to protect its own interests, the Monroe Doctrine advanced the United States’ authority over Latin America. Presidents throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century invoked the Monroe Doctrine, and in some instances expanded its scope and meaning, to pursue expansionist goals and solidify their power in the western hemisphere. James K. Polk, for example, was the first to draw upon the Doctrine’s language during the Mexican War. Theodore Roosevelt famously amended the Doctrine with the Roosevelt Corollary, which justified military intervention in Latin America. John F. Kennedy also cited the Doctrine to oppose Soviet pressure during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

These sources show the formation of America’s new foreign policy. In a letter dated October 17, Monroe asked Thomas Jefferson for advice on how best to pursue George Canning’s proposal for an alliance. Jefferson’s response a week later encouraged Monroe to agree to it, considering Monroe’s dilemma the greatest since their pursuit for independence. The excerpt from Monroe’s congressional address, the Monroe Doctrine, is Monroe’s, and the United States’, answer to this “momentous” diplomatic question presented before the country.

Document Based Questions

James Monroe to Thomas Jefferson, October 17, 1823 (Courtesy of the Library of Congress) View

- How did George Canning suggest Great Britain and the United States could defend South America from the holy alliance?

- What questions and considerations did James Monroe have regarding George Canning’s proposal?

- What does James Monroe ask of Thomas Jefferson?

Thomas Jefferson to James Monroe, October 24, 1823 (Courtesy of the Library of Congress) View

- Why did Thomas Jefferson consider this “the most momentous” question since declaring independence?

- Why would an alliance with Great Britain benefit the Untied States?

- What were the tenets of the “American system” Thomas Jefferson advocated for?

- Why did Thomas Jefferson consider the acquisition of Cuba favorable to the Untied States, and why was this consideration unrealistic?

- What course of action did Thomas Jefferson suggest James Monroe should take towards the British government?

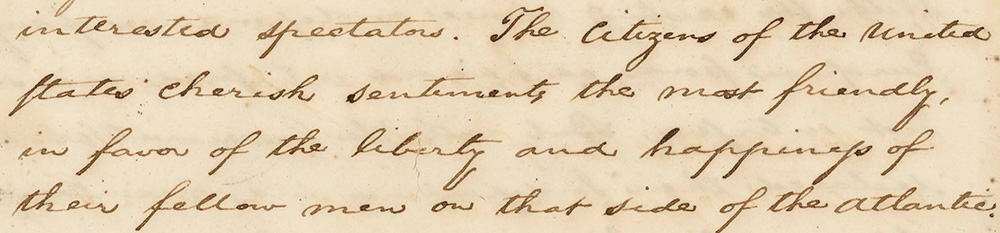

The Monroe Doctrine, 1823 (Courtesy of the National Archives) View

- Why would America need to make preparations for its defense?

- How will the United States engage with independent nations and European colonies in Latin America differently?

- What four goals did James Monroe establish regarding America’s foreign policy towards Europe?

- At the end, what did Monroe define as the “true policy” of the United States?

Essential Questions

- Why did the United States alter its foreign policy during the early 1820s?

- How could an alliance with Great Britain be both beneficial and harmful to the United States?

- How do these primary sources reveal James Monroe’s decision making abilities as president?

- What is the Monroe Doctrine’s legacy in American history and today?

Virginia Standards of Learning

CE.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

d) determining the accuracy and validity of information by separating fact and opinion and recognizing bias.

USI.7 The student will apply social science skills to understand the challenges faced by the new nation by

c) describing the major accomplishments of the first five presidents of the United States.

USI.8 The student will apply social science skills to understand westward expansion and reform in America from 1801 to 1861 by

a) describing territorial expansion and how it affected the political map of the United States, with emphasis on the Louisiana Purchase, the Lewis and Clark expedition, and the acquisitions of Florida, Texas, Oregon, and California;

National Standards for Social Studies

Era 4 Expansion and Reform

Standard 1A

Grades 5-12 Identify the origins and provisions of the Monroe Doctrine and how it influenced hemispheric relations. [Reconstruct patterns of historical succession and duration]

Standard 1C

Grades 7-12 Explain the diplomatic and political developments that led to the resolution of conflicts with Britain and Russia in the period 1815-1850. [Formulate a position or course of action on an issue]

Bibliography & Suggested Readings

Combs, Jerald A. “The Origins of the Monroe Doctrine: A Survey of Interpretations by United States Historians.” Australian Journal of Politics and History 27, No. 2 (August 1981): pp. 186–196.

Gilderhus, Mark T. “The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 36, No. 1 (March 2006): pp. 5-16.

Moats, Sandra. ‘President James Monroe and Foreign Affairs, 1817-1825: An Enduring Legacy.” in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, ed. Stuart Leibiger. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2013. pp. 456–471.

Poston, Brook. “‘Bolder Attitude’: James Monroe, the French Revolution, and the Making of the Monroe Doctrine.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 124, No.

4 (2016): pp. 282-315.

Scherr, Arthur. “James Monroe on the Presidency and “Foreign Influence”: From the Virginia Ratifying Convention (1788) to Jefferson’s Election (1801).” Mid-America Historical Review 84, No. 1-3 (2002): pp. 145-206.