Why

When recording the history of plantations and slavery in America, narratives typically focus on white enslavers and make generalizations about the impacts of enslavement. These narratives conflate the experiences of enslaved people and focus solely on the past without understanding how legacies play out today. The individual lived histories of enslaved people and their descendants therefore get little recognition. These communities face even more erasure in the broader study of history. Such narrow approaches fail to represent the struggles, strengths, and innovations of descendant communities, who are integral to the American story.

In order to produce a more complete history of the United States and of enslavement, we must recognize and learn from those who are impacted by its legacy, but these voices have so often been ignored. This means highlighting the diversity and complexity of descendants’ stories, including as they relate to food, community, and land. By recording the accounts of Highland descendants, we hope to provide a more complete view of plantation legacies, food histories, and lived experiences.

Background

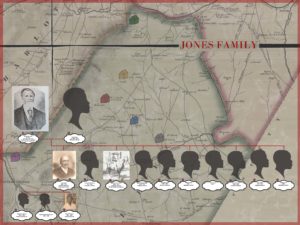

Highland is the site of former-president James Monroe’s plantation where he enslaved 178 individuals. Generations later, there is now an active descendant community working to reclaim their families’ histories. There are two primary groups of Highland descendants — those centered around Albemarle County, Virginia and those in Jefferson County, Florida, where their ancestors were forcibly moved in 1828. The families in Albemarle County largely remained in the same area for the 150+ years following enslavement. Documenting these families’ stories will provide a more complete history of Highland through the legacy of the plantations on the food, community, and culture of the descendant communities today.

Highland descendants show a deep attachment to the land they grew up on and the Charlottesville area as a whole. Though some have moved away, their connection remains and many hope to one day return. For lots of the descendants, this connection has been fostered by the practices and traditions their families engaged in on the land itself. Almost every descendant family raised produce and animals for healthy, sustainable, and accessible sources of food. The dishes cooked by the descendants combining such local ingredients and cultural innovation have been passed down from generation to generation. And these traditions demonstrate how the descendants’ land and the food they ate were intertwined with the fabric of their own identity and their family’s as a whole.

The Project

This project emerged in partnership between Highland, the Highland Council of Descendants and the William & Mary Institute for Integrative Conservation. During the summer of 2022, Bridget O’Keefe, Anna Arnsberger, and Josiah Tunstall worked alongside the Highland Council of Descendant Advisors to conduct oral histories within the descendant community. The interviews centered on foodways — the traditions and cultural practices related to food.

This is the beginning of a broader effort to document and uplift stories of historically-underrepresented communities. Through conversations with descendants, and celebration of food, tradition, and connections to land, an opportunity to call attention to underrepresented groups emerges. We hope this research can also be used as an educational resource