Slavery was ingrained in the fabric of the early United States and was central to the operation of Highland. Scores of enslaved women, men, and children lived on the property between 1799 and 1865, with 53 unfree people at Highland under Monroe’s ownership. These artisans, domestic workers, carpenters, cooks, and farm hands had deeper, more complex connections to this place than did Monroe himself who was often away in public office. From historical records we know of 178 individuals who led their lives—in part or wholly—enslaved by Monroe during his adulthood. He freed only one: Peter Marks, who was manumitted in a request Monroe made during the last days of his life.

Monroe represents an inherent contradiction, keeping dozens of individuals enslaved while calling for the abolition of slavery. In an 1829 letter, he described slavery as “one of the evils still remaining, incident to our Colonial system” (Monroe to John Mason, 31 August 1829). Abolition, he thought, should be gradual to avoid disrupting the social order and economy. He advocated and actively worked for the resettlement of newly freed Blacks in Africa. The concept of such African settlements acknowledged a lack of belief in, and fear of, an American society in which Black people and white people could participate equally. Monroe affirmed this view in his letter, writing that he had “always been friendly to an emancipation, and transportation from the country” but he believed that free Blacks would “become a publick [sic] burden, if considered and treated, a portion of the community.” (Monroe to John Mason, 31 August 1829)

Monroe’s moral discrepancy shows him to be a man of his time: on the one hand aspiring to virtue and justice, yet never abandoning prevalent views and practices. Although there were individuals who moved beyond these views in their time, Monroe did not. It is important to look directly at figures like Monroe and consider their role in creating and perpetuating an unjust and inhumane system whose legacies we still live with today, along with their contributions to the development of the U.S. government.

Highland’s story reminds us of the ways the history of the United States is profoundly connected to the institution of slavery. Enslaved labor enabled the economic development of the new nation. At Highland enslaved workers carried the knowledge of and responsibility for agriculture. The legacy of slavery is continually present in our communities today in systemic inequalities. Confronting the United States’ fraught past can give us better tools to understand and address today’s issues. The perspectives of enslaved men and women are as crucial as those of presidents to understanding this nation. At Highland we strive to represent a multivocal history, one in which many voices combine to tell one set of stories.

To learn more about enslaved individuals who worked and lived at Highland, visit https://highland.org/enslaved-biographies/.

1794

The families James Monroe and Elizabeth Kortright Monroe were enmeshed in the economy of slavery. The president grew up on a tobacco farm worked by enslaved people. He inherited legal human property at age sixteen (1774), when his father died and bequeathed to him an enslaved boy named Ralph and a number of enslaved farm hands whose names are unknown.

Enslaved women and girls, often at a very young age, were taken away from their homes to attend white women who made elite marriages. They typically had no means to communicate in writing, and were unable to stay connected to parents and siblings they left behind. We do not know whether an enslaved girl or woman was forced to leave her family in New York to accompany Elizabeth Monroe to her new life in Virginia at the time of the Monroes’ marriage.

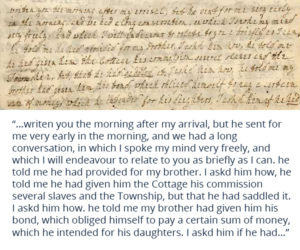

One of the two surviving letters Elizabeth Monroe wrote references individuals enslaved by the Kortright family. In 1794 Elizabeth wrote to her husband of the scope of her inheritance, which included “several slaves.”

1800

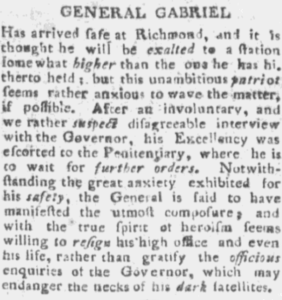

During Monroe’s first term as governor, an enslaved blacksmith successfully garnered tremendous support in an insurrection employing revolutionary language familiar to members of the United States’ founding generation. “Gabriel’s Rebellion” began on Thomas Prosser’s plantation west of Richmond, and drew support from enslaved men from the city of Richmond and surrounding counties, stretching into Henrico County and further afield into Caroline, Louisa, and Hanover Counties. When the plot was revealed to the authorities, Monroe quickly mobilized the militia and thwarted the insurrection. After the resulting trials—written about in newspapers like the one shown—Gabriel was one of 26 men who were hanged before Monroe freed dozens of other enslaved activists (for the famous severity vs. mercy discussion, see Monroe to Jefferson, 15 September 1800).

The event resulted in increased legislative restrictions on enslaved education, assembly, and hiring-out, and it influenced Monroe’s views on slavery for the remainder of his life. Like many other whites, he feared violence from other rebellions, yet could not imagine sharing American liberty with free Blacks.

1810

The 1810 Albemarle County, Virginia census showed Monroe to be one of the county’s largest slave-owners at the time, with 49 enslaved adults living at Highland. Of the more than 1,500 households in the county that year, only fourteen had larger slave inventories, including Thomas Jefferson’s at Monticello, which held the most at 147. Highland’s enslaved population included field workers and skilled workers (blacksmiths, carpenters, masons and “house servants” like valets and maids, and a cook and her assistants). While Monroe was often away pursuing law and politics, the enslaved workers maintained Highland’s day-to-day operations and became intimately familiar with the surrounding countryside.

1822

Monroe supported colonization as a means of gradually reducing and ultimately abolishing slavery in the United States. He exchanged ideas on the topic with Thomas Jefferson beginning in the early 1800s. In 1817, Monroe’s first year as president, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was formed. Five years later, Liberia was established as a place where freed slaves from the United States, as well as Africans captured on foreign slave ships, could be resettled. Because of Monroe’s endorsement of the ACS, Liberia named its capital, Monrovia, after him.

1826, March

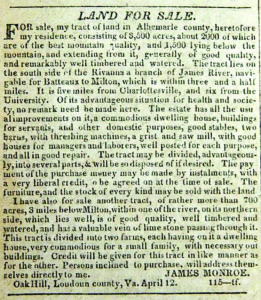

As the South’s economic engine shifted to cotton by the 1820s, Highland’s profitability—which came from grain—plummeted, with dire consequences for enslaved field hands. Since cotton does not grow in the Virginia Piedmont, Monroe and neighboring farmers were left behind. Facing potential financial ruin, he listed Highland and his Loudoun County property, Oak Hill, for sale in the Richmond Enquirer. He first sold the house at Highland, and later its farmland, said to be of “the best mountain quality,” in close proximity to Charlottesville and the University of Virginia, which had just opened (in 1825).

Sale dispersed a number of enslaved African Americans locally in Albemarle County, and to Florida.

1826, July

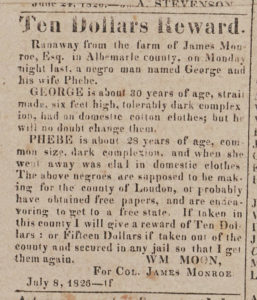

Threat of separation from home and loved ones was a constant factor for Highland’s enslaved population. Among the difficulties the enslaved community endured was instability caused by frequent transfers between Monroe’s two properties according to work needs. Families were often split up in such moves, and maintaining human was made even more challenging than the framework of slavery ordinarily demanded. An enslaved couple named George and Phebe were among those who risked their lives to escape the conditions under which they lived. After the pair ran away from Highland in July 1826, Monroe placed an advertisement in the local newspaper offering a reward for their return. We do not know whether they achieved freedom.

1828

When Monroe sold the Highland farmland in 1828, many of Highland’s enslaved men, women, and children became part of the larger wave of labor sold to the Deep South. Those sold south went to a cotton plantation called Casa Bianca in Jefferson County, Florida. Monroe gave directions that the buyer, Colonel Joseph White, keep existing families together. Recent documentary research indicates that several couples and their children did indeed make the journey together. You can trace their stories through this external link: https://taketheminfamilies.com/stories-2/.

1908

There was a three-room dwelling (a triplex), thought to be an antebellum quarters, that remained intact at Highland until the 1920s. A reproduction was rebuilt in the 1980s based on the 1908 photograph shown here. The architectural details shown in the photograph suggest that the building dates to the 1840s or 50s. There was likely an earlier quarters in the same location.

Research at Highland continues, uncovering enslaved people’s names, relationships, backgrounds, and their contributions to the presidential property. To learn more about the people enslaved by Monroe, and their descendants, please explore the growing list of links below:

Documentation of enslaved individuals who worked and lived at Highland, visit https://highland.org/enslaved-biographies/.

Resources beyond the Highland website reveal more about people enslaved by Monroe and their descendants. A growing list of outside links is started below.

Documentary mentions of people enslaved by Monroe are chronicled on the Thomas Balch Library website: https://www.leesburgva.gov/home/showdocument?id=8851/.

The stories of several families continue after a number of enslaved men and women were sold from Highland to Florida. To see work by a team of independent researchers, visit: https://taketheminfamilies.com/.

Visit the White House Historical Association’s website to read The Enslaved Households of President James Monroe by Matthew Costello: https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-enslaved-households-of-president-james-monroe.

Do you have family history you would like to share with us? Contact us at info@highland.org.